Advancing Midwest Defense Innovation: A Fireside Chat with Senator Todd Young

10.29.24

Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy CEO Michelle Giuda moderates a fireside chat with U.S. Senator Todd Young at the Midwest Defense Innovation Summit on Oct. 16, 2024, hosted by the Applied Research Institute.

The Midwest Defense Innovation Summit is a premier event organized by the Applied Research Institute to showcase the defense innovation ecosystem in the Midwest. Held at the Indiana Convention Center in downtown Indianapolis Oct. 16-17, 2024, the Summit brought together key stakeholders, policymakers, industry leaders, and regional partners to hear the latest innovations and foster opportunities to collaborate. Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy CEO Michelle Giuda conducted a fireside chat with U.S. Senator Todd Young in this Summit session on Oct. 16, 2024.

Full Transcript:

Michelle Giuda: All right. We’ve had a tremendous day here in talking about the Midwest being such a critical node in the global trusted tech network in the field of defense innovation. So I want to start out with a little bit of a big picture question here because we’ve talked about so much. But if you look at what’s happening across the world when it comes to defense and innovation and technology, Russia, in Ukraine, has used for the first time a hypersonic missile. China, CCP hackers are now in our critical infrastructure: water, telecommunications, power. Iranian-backed Houthi rebels are using very cheap drones to disrupt commercial trade in the Red Sea. So we see all sorts of new technologies being used by many of our adversaries across the world. When it comes to the Midwest, what is the necessary—what is the critical role that the Midwest has to play in making sure that we’re competitive in this type of arena?

Senator Young: Well, thank you, Michelle. Thanks for the question, and thanks for hosting this forum, which is, of course, focused very directly on this topic. Listen, for years, conversations around national defense have started and usually remained on the coasts, and the Midwest has been an afterthought, if anything, which is sort of peculiar when you think about it. You look at our assets across the Midwest. This used to be known as the industrial Midwest, and that’s still oftentimes how I think about it. I mean, we make things, and increasingly we’re looking to make more high-value-added things as we move up the value chain. And I think the DOD, I think Congress, and allies and partners alike should look to America’s industrial Midwest to make technological things. I share the Governor’s vision. I know it’s President Chiang’s vision at Purdue, and that of others, of trying to make the Midwest—this is more narrowly circumscribed to the state of Indiana—but trying to make it a hard tech corridor for our country and for our allies and partners. So, that’s one area in which I feel like the Midwest can excel.

We have world-class research universities, again historically. They have built up certain expertise in areas that are informed by the economies and the needs around them and the aspirations of the people. And so we’re great at biotech. At Purdue, much of that biotech is focused on the ag economy. Indiana University is also very strong at biotech. There’s this focus disproportionately on the health sciences. We’ve seen biotech, as I look at Representative McCollum over there—we’ve seen biotech, because she’s played such a leadership role as it relates to BioMADE and that whole initiative at the federal level. But this is now an important national security field. It’s an emerging tech field. Here again, the industrial Midwest can play, I think, an outsized role in filling some of the gaps.

We need to leverage the capabilities we already have, as we do in any other sector of the economy. What skills have our people been trained on for a number of years, whether it’s through our community college system, Ivy Tech, or through our other universities? What existing incumbent businesses do we have here, not just manufacturing but others? And so, let’s leverage those. Let’s also leverage the research experience that exists in our universities. And there are some discrete fields that are uniquely strong in the Midwest, and energetics is one of those fields, for example. So, let’s continue to double and triple down on those things. I think if we do that, we will find ourselves continuing to be an important part of the conversation as our military leaders in particular look around to figure out how we’re going to manufacture all the things that right now are facing constraints, but we have some industrial base here to tap into to help provide those things to our warfighters and others.

Michelle Giuda: So, you talk about all the areas that the Midwest is leading. Chips is one of them, yes? And, you know, you’ve been such a tremendous partner to us at the Krach Institute for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue. Our founder, Keith Krach, had the opportunity to work with you on some of the original ideas that eventually turned into the CHIPS legislation.

Senator Young: He was an amazing leader, and if needed, I’m sure he may be prepared to suit up again in service to our country. I hope that’s the case.

Michelle Giuda: Yeah. And if you think about what CHIPS has done—and chips are important because we’ve talked about almost every conversation today has to do with chips. They power everything with an on/off switch from iPhones to F-35s. And if you think about what CHIPS has done, the CHIPS legislation has done so far, I know Secretary Raimondo highlighted that by the end of this decade, we’re going to be on track to produce 20 percent of high-end logic chips. And that’s a big deal because it’s up from zero before the CHIPS legislation. And the Midwest is really important because you’ve got the Silicon Crossroads, Microelectronics Commons that our hosts here today, the Applied Research Institute, are leading. Purdue is a part of that. It’s also attracting foreign investment. SK hynix did a $4 billion investment in Indiana at Purdue Research Park, one of the largest economic development projects, all as a result of this legislation that you had led. How are you thinking now about the other piece of the CHIPS Act, which is R&D and workforce development? Because that needs a Midwest hub too.

Senator Young: Yes. So, the CHIPS portion of the CHIPS and Science Act has received a lot of attention. In fact, we often will call the CHIPS and Science Act the CHIPS Act, and I stubbornly clung to the longer title for the longest period of time because I actually, from the beginning, regarded the “and science” piece to be every bit as impactful, perhaps even more consequential in the long run to our country’s economic growth, to our material prosperity, to defending our way of life as I do the semiconductor piece. So yes, we’ve unlocked $450 billion of capital. We’re the only country in the world that has been able to locate all five leading-edge semiconductor companies here on this soil. But the objective there was never to become fully independent of the rest of the world. So now that we are on a trajectory with continued successful implementation to ensure that we take the risk out of our supply chains that we aimed to do working with our partners and allies, I think we really need to turn our focus to resourcing these other areas of emerging technology. And some of them arguably could be characterized as general-purpose technologies. Areas like artificial intelligence and emerging biotech—they will enable all sorts of new things to occur in our economy that are very difficult to predict right now. And we also sense that once scaled, they will be the keys to continued global leadership from a national security standpoint and also to our material prosperity.

So, Congress, understandably and appropriately, is right now taking a very close look at our income statement versus our commitments moving forward, and we’ve got to make some hard decisions. But it’s always a bad decision when you’re a business to take away your growth areas when you’re feeling some heat from the market, and I don’t want us to do that. I want us to continue to invest in those areas that will be drivers in our economy. Think of just emerging biotech. It will drive continued ag growth and pharmaceuticals in the future, but it’s much broader than that. We actually have the ability—and this here is where the Midwest can really excel—we have the ability to leverage our biotech expertise to make all kinds of things for industrial and commercial applications that we’ve never made before through the wonders of biotech. And everything from new ways to make leather out of the biological qualities of mushrooms to new materials for our warfighters so that they’ll be more resistant to kinetic attacks, to artificial blood, and on and on. So, we’re just sort of getting started here, and the Chinese are doubling and tripling and quadrupling down on their investments. All we have to do is unlock our potential. Most of what will be required is not a direct allocation of resources, although some of that will be required. Instead, we need regulatory harmonization. We need to make sure that we shift our fire in terms of how we train our workforce so that we have more people prepared for this field. Same thing on artificial intelligence. It’s not going to take a lot of money, but there are things that Congress has to do to prepare us for this 21st-century world.

Michelle Giuda: I love that you’re talking so much about biotech because it is such a unique area for the Midwest. You know, we had NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoană. We hosted him at Purdue University in April of this year. When you think about defense innovation and the role that the Midwest plays, it’s significant that you had the Deputy Secretary of our defense alliance here in the Midwest, and one of the things that he was very focused on was biotech and how NATO is seeing that as really important to the defense alliance.

Senator Young: I also emerged today, just an hour ago, from a meeting of the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotech, on which I sit. I’m now the chairman of that commission. We’ll be producing a report of our recommendations for congressional action here in the next few months, and so it’s very much top of mind. But the more I learn about the opportunities there, in addition to artificial intelligence, which I think most everyone here is familiar with those value propositions, I’m just amazed by the possibilities if we don’t screw things up by taking overly prescriptive action and constraining with regulation some of the natural innovation that’s going to occur through our market economy, but also by failing to take some affirmative acts in different areas like investing in shared infrastructure for startups to go in, to test their their ideas, validate their ideas, and then scale where those ideas work.

Other countries are already making these investments in Europe, in Asia. I’ve seen them in my travels. We need to up our game as well. And I will add, because my friends from ARI are here, and I’ve been so impressed by their work over the years, we have an opportunity to get a bit more of a head start. Not only do we have Eli Lilly and Corteva and Elanco and Purdue and IU, but we’ve now been designated a federal tech hub, which will be funded to assist with biomanufacturing here in the central Indiana area. So, it’s an exciting opportunity for the region to play an outsized role in this field.

Michelle Giuda: I’m glad you brought up this dynamic between the public sector and the private sector and how we have to get that balance right. One of the things that I’ve said—and I said this at the Global Economic Summit here in Indianapolis earlier this year, and maybe you agree with it, maybe you don’t—but one of the things that I said is, this is ultimately a tech race, right? We’re in a tech race with our adversaries that are also building up in these technologies like AI, and they want to dominate them, China in particular. But that tech race isn’t going to be won in Washington, D.C. It’s not going to be won in Brussels, and it’s not going to be won at the UN. It’s going to be won right here in Indianapolis or in Milwaukee or in Cleveland because this is where our innovators and our enterprises are. But talk through that unique balance between, because we’re talking about defense and innovation—we’ve heard from public sector, we have a lot of private sector leaders here—but what is that right mix so that we get national security right?

Senator Young: Well, we need to consistently be asking the private sector, “What do you need?” The job of government is to cast the vision and say, “We see a collective value proposition in this technology,” or, “We see a vulnerability that we have not yet seen the market address in this area,” and then tease that out with as much specificity as you can for your amazing innovators, entrepreneurs, and capital markets, which we have, and then ask, “What do you need to create a solution?” And if the answer is, “Well, you need to reshape the market a little bit so that the hurdle rate on my investor’s investment changes and this can be a cash-positive investment,” then we need to consider that. If they say, “You need to take a look at the research and development tax provisions. It doesn’t make sense for us to locate that sort of research-intensive enterprise in the United States,” then we’re going to have to up our game in that area. If instead they say, “The market has just not evolved as it relates to a particular technology enough; we need government R&D upstream before government can take the ball,” then let’s take our direction from the market economy once we articulate to folks exactly what solutions we want them to solve.

I’ve always regarded that as the unique strength of our system as compared to a state capitalist system. I marvel, like everyone else, at the ability to marshal capital to focus the minds and attention of an entire country of a billion-plus people. I mean, that’s the Chinese model. It’s impressive, and sometimes it yields real dividends. But I think in the long run, if we just focus on becoming a better version of ourselves—which is what we did in the Cold War—there is no way we can lose–we can lose this race.

There are three things that I think of we don’t want to do. We don’t want to tribalize ourselves and therefore paralyze ourselves against taking bold action when it’s required. Sometimes we seem to tread precariously close to that, but we’re going to get through this election. We’ll come together. We’ll start to get some important things done. We don’t want to alienate any of our allies. I mean, it’s just—it’s not China versus the United States. I think that is the wrong paradigm. It’s like most of the world against China, if we play our cards right, because our values are attractive. We are good friends. We are good partners. So, we need to enlist the help and assistance and partnership of those around the world. And then the last thing, let’s not screw up a general-purpose technology. Like if we overregulate in these early stages artificial intelligence or we do the same thing with emerging biotech or just fail to do obvious things that are required to catalyze more innovation and then deployment of these technologies, that could really jeopardize our future as well. But if we don’t do those things, we win. We win. So no pressure, right?

Michelle Giuda: Three easy things. I’m glad you mentioned our allies and making sure that we don’t alienate them, because I do want to talk a little bit about diplomacy. I know this is the Defense Innovation Summit, but defense and diplomacy are inextricably linked, because if we do diplomacy right, we don’t have to marshal the arsenal.

Senator Young: I’m so glad you said that, yes. And defense is a broader construct than just the DOD. I chose not to be on the Armed Services Committee. Some of you think, “Why?” God, it’s awesome. I didn’t want to deal with the bureaucracy, and I also saw opportunities to advance foreign policy on the Finance Committee: trade policy, international tax policy. The Commerce Committee: tech policy we’ve done through the CHIPS and Science Act; we need to do more with the Science piece. There’s other opportunities, from quantum to you name it. So, I really think it’s important that we start to have a broader sense of what constitutes defense. But you were leading into a question, weren’t you?

Michelle Giuda: Yes, I—no, but this is a great—you made my preamble better!

Senator Young: No, please go ahead.

Michelle Giuda: But so, I want to talk a little bit about diplomacy. Yes, you’re on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. You’ve actually done some travels internationally pretty recently—Taiwan, Korea, South Africa, Mexico, Canada. You’re an honorary co-chair on our Global Tech Security Commission, where we’ve got 15 of our closest techno-democracies working together to secure critical tech. But as you travel around the world, as you engage in your work on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, what role do you see diplomacy playing in making sure that we’re innovating in the right ways? How can we be working with our allies in Europe, across NATO, the Quad, in Latin America, where they’re really emerging? How can we be doing that in order to strengthen our national security?

Senator Young: Well, Michelle, this is why I am so grateful for—and this was not rehearsed—so grateful for your leadership and for Keith Krach and for the Krach Institute. It’s not enough for us to just say, “China, China, China,” and think we’re going to win the 21st century. Our best sales tool, don’t get me wrong, is probably China. It’s Communist China. It’s the fact that they don’t share our values. They don’t have real allies or friendships; they have vassal states. They don’t share our enlightenment values that apply to all mankind. We know that, but it’s not enough. We have to offer them an alternative when it comes to specifics. Great example is Huawei, yes? Through the heroic diplomacy of many of our diplomats, and of course, Keith led the charge within the State Department on this, we were able to unwind these sunk costs of Huawei investments through the rip-and-replace efforts. But we still don’t have a lot to offer them as an alternative. This is where our government has lost sight of its role. We need to insist that the private economy produce an alternative, and then we need to ask, how do we get you to produce an alternative? What predicates do we have to lay? How long is it going to take? How might we expedite things?

We tend to do this very well in emergency situations. Think of COVID, right? We did it very well. But let’s not wait for emergencies. It’s a hell of a lot cheaper if we dig our well before we’re thirsty, and we really have an opportunity here to dig this well across the Midwest, where your bang for the buck is going to be incredible. Your return on investment, I would argue, across the Midwest is going to be higher oftentimes than in other locations where, over a number of generations, the weight of investment in those geographies has been considerable.

Right now, there’s been a lot of reporting and hand-wringing and finely focused minds as it relates to our defense industrial base. And I mean, that all comes back to the Midwest. This is where the real capacity continues to exist, and this is where I hope much of the investment comes. But frankly, we shouldn’t be in this Great Leap Forward posture. Occasionally you have to when you miss things. But the early warning signal to everything is our diplomats. They are the ones who report on the activities of foreign governments with our intelligence community. They are the early warning signals that work with allies and partners to crowd in more capital, to coordinate research, development, commercialization, production of different things.

So again, as we think about the role the Midwest might play, it’s not just going to be the role that the Midwest might play to provide for the common defense of the United States. It’s going to be a role that the Midwest can play globally to protect our enlightenment values against those of predatory capitalists and autocrats like Xi Jinping.

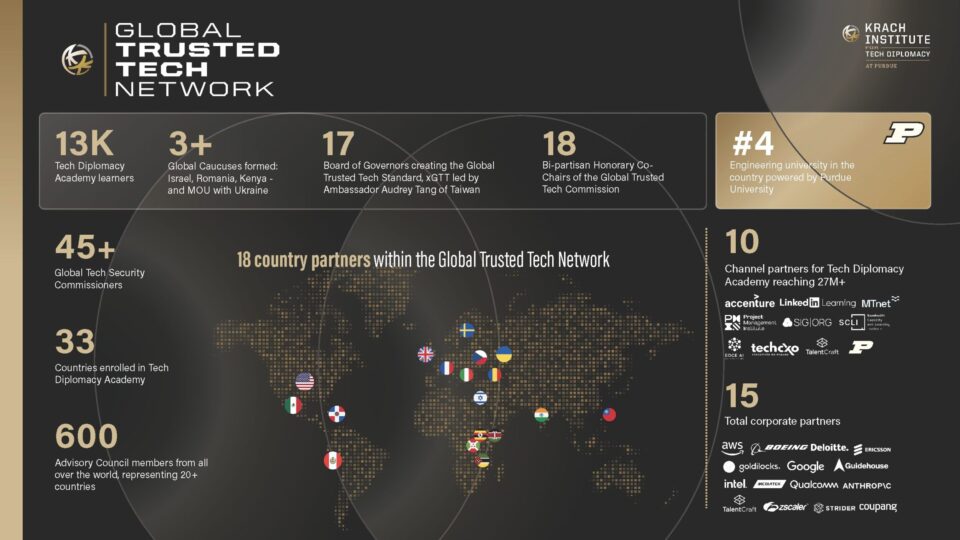

Michelle Giuda: One of the things that we’ve talked about a lot today, in almost every session, speaking of things that we don’t want to let get to emergency level but as close, is workforce development and upskilling and reskilling when it comes to new technologies and manufacturing, and how universities in the Midwest, companies in the Midwest, are really focused on that. Then, that relates to actually what you just said as well about our diplomats, because there is an upskilling of diplomats that’s also needed when you think about all of the different technologies that they need to be able to understand to report that back home. And we were really proud to launch the Tech Diplomacy Academy out of Purdue as another way that Purdue is teaching our U.S. government officials and business officials to compete.

Senator Young: Yeah, Michelle, you were there when Secretary of State Blinken and Secretary Raimondo, our Secretary of Commerce, visited Purdue. And Secretary Blinken said, “You know, this place is a human fab. You produce engineers and technicians.” And he was speaking more broadly about Purdue and its partnerships and what Indiana’s focused on, but you’re producing people. We need to do that in every major university that has capacity and every community college that has capacity. Prepare our workers for the 21st century, allowing them to provide better standards of living for themselves, for their families, and meaningfully contribute in this dynamic economy. It’s all people are asking for. And so, we just need to ask something of people in this precarious time globally: to step up and add value.

And as it relates to our diplomats, I’ve got to tell you, the Krach Center is doing amazing work. I’ve spent the last year and a half traveling to a lot of countries, mostly around the Asia-Pacific. And when I go into these embassies, they have entire teams now—it’s a very recent development—of tech diplomats, and they’re focused on interfacing with semiconductor companies, support companies, government officials, and of course, those within our own government, figuring out how we can coordinate research, development, commercialization, production of different components along this ramified supply chain. That was how the CHIPS and Science Act was supposed to work. And I’ve got to tell you, I didn’t know whether all of this would come together. It’s an incredibly complicated exercise, but there’s no way we could have pulled this off but for having very well-educated and prepared tech diplomats.

We can do it better next time now that we have the infrastructure being developed by the Krach Academy. We won’t just want to do it in the area of semiconductors, but I’m starting to have diplomats ask me, “How can I get trained on emerging biotech? How can I get trained on artificial intelligence?” Or ambassadors indicating that we need more personnel that have these areas of expertise. And then, if you have people who can talk the talk, people who actually understand the technology enough to have an intelligent conversation, then we can work with other countries and stakeholders to engage in the diplomacy required not just to embed our values within these technologies—values related to privacy and consumer protection and openness and transparency, as opposed to the Chinese Communist Party’s values—but actually technical standards that advance those values.

So, if you can harmonize the non-Chinese AI standards, for example, and if China wants to sell into the rest of the world and get the scale necessary to really have viable, long-term AI businesses, they need to abide by and produce for our market. This is incredibly powerful, and we’re in the process of doing this right now. But we couldn’t do it if we didn’t have the right sort of trained diplomats,

Michelle Giuda: And it’s great that the Midwest gets to play a leading role now in upskilling the State Department and the U.S. government.

I think we have two minutes now, last question. We’ve talked a lot about new opportunities in defense innovation, all of the strengths here in the Midwest, the opportunities and the promises of new technologies. But we’ve also talked a lot about headwinds, not just about what our adversaries are focused on or the CCP, like you had highlighted, but some of our own internal problems that we need to fix and get right. Building ships, for example—we’re drastically behind in our capacity to build, repair, and maintain ships for our U.S. Navy. We talked earlier about the debt and how we’re spending more on servicing our debt versus the U.S. military. So, there’s some of these fundamentals that we have to overcome at the same time that we’re trying to think on the next horizons about innovation. So, as a final question, how can the Midwest really lead on getting those fundamentals right and being a leader in this new frontier?

Senator Young: Of course, I’m highly biased, but I like to think that those of us in the Midwest have at least a measure more common sense, if you choose any given issue, than folks from other regions of the country. Not always the case, but I think we’re sort of known for that. We don’t get caught up in faddish intellectual movements as often. We’re just practical people, and that lends itself to common sense. How is common sense helpful? Well, think about our fiscal situation. Debt to GDP—I don’t care how much debt an individual owns, has on their household balance sheet. It’s irrelevant to me; it means nothing unless you know how much income they have coming in, right? So, debt to GDP is the only number that really matters.

Let’s not take away the seed corn for our future growth. So this gets to the “and Science” portion, but other things as well. Let’s continue to invest in requisite skills, etc. Yes, let’s scrutinize everything. Let’s make the largest programs of government sustainable and talk unapologetically and very specifically, as I’ve tried to do, about the need to make Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid solvent, for example. So, we need to do that. We need more free trade agreements. There’s a national security lens through which you could talk about this, but fiscally it’s important. We need legal immigration, especially high-skilled. It makes no sense that we will educate someone at the University of Notre Dame in some of the most in-demand fields, and we send almost all of them back. We not only need to retain them, we need to retain them in the state of Indiana, where possible, so that we can have more world-class businesses locating in the industrial Midwest.

So, that common sense, I think, is going to be really helpful in the coming couple of years as some of these decisions are going to come to a head. And then, you know, you mentioned ships. Jerry Hendricks has taught me so much on this issue. I know you heard from him or will hear from him, and one of the most compelling value propositions I think we have in the Midwest to play a constructive role in helping address this is—listen, we know there are some major DOD shipyards out there. They’ll continue to build ships, still play a really active role. We want them to do well. But there are places in the Midwest where we can make components of many of those ships, and so let’s tap into that value proposition.

And then let’s think a little more boldly. I mean, we need a labor force that’s at the ready to help build these ships on a regular basis. We also need more merchant vessels. So, maybe we construct more merchant vessels across the industrial Midwest, and when they’re not building merchant vessels, they can spin off and construct Navy ships as we try and rebuild our Navy. So, I suppose that comes back to common sense, but that one wasn’t intuitive for me. And I think, between the industrial base and a measure of common sense, and harnessing the existing people and assets we have, this is the Midwest’s time to play an outsized role in national defense innovation in the 21st century.

Michelle Giuda: Well, thank you, and thank you for your leadership in making that a reality, that it is, in fact, the Midwest’s time. And thank you for your time today. Your leadership has not only been common sense, but it’s also been quite visionary. And so, thank you for all of that. Thank you for being a partner to the Krach Institute and for helping the Midwest to be a global leader.

Senator Young: You’re welcome. Thank you for your role, everyone, and if there’s anything you feel like Congress ought to be involved in, that you don’t feel like we’re sufficiently attentive to, please contact my office. We’d like to legislate; we like to solve problems. We would love to work with you on solving these incredible challenges we’re facing. But I think they’re all overcomable. So young.senate.gov is my website, and for those that are visiting from out of state, please spend a lot of money while you’re here. God bless.

Audience: [Laughter and applause]